Chapter 8 - Core Business Concepts

Section II - Modelling

As I said in the previous chapter I cannot take any credit for the ELM approach nor can I claim that I have represented it faithfully in these articles. If you wish to learn more about the technique you should reach out to Genessee Academy.

By now, you should have a fairly strong sense that core business concepts (CBCs) are really important and especially important to the HOOK methodology. The problem is that CBCs can be difficult to identify, especially when confronted with a blank sheet of paper. Furthermore, even if we are able to identify them, we will, most likely, get some of them wrong.

But we have to start somewhere, and the ELM approach is a relatively gentle way to approach the task at hand. When I learned about the ELM methodology, it struck me that it is a data modelling technique for people that aren’t data modellers - as a data modeller, I’m not quite sure how a feel about that.

ELM CBC Process

There are four basic steps in the ELM process for identifying and capturing CBCs. Ideally, this should be done in a workshop environment, preferably in person in a room that has copious (whiteboard) wall space. However, in our post-COVID world, remote or virtual working has become the norm, and there are plenty of online tools out there to facilitate collaborative working over the internet.

Before I dive into detailing these steps (and it won’t take long), I need to stress that identifying CBCs is a business-focused exercise. This means that the people we need to talk to are people from the business. The people that deal with the interests of the organisation's customers. It is those people that need to be in the room for the CBC workshops. But which, and how many, people do we need in the room? The answer to that question is “It depends!” but let’s make some assumptions. Let’s call this Step 0.

Step 0 - Pre-requisites

First of all, it is unreasonable to think that we can model the entire organisation in one go. For a start, it would be next to impossible to identify, let alone organise, all the relevant people into the same workshop session. The number of people would be too great, and trying to gain consensus across the group would be extremely challenging. You want to avoid long, drawn-out debates, and the more people you have in the room, the more likely they are to occur.

Although creating an enterprise-wide model is the ultimate goal, in practice, we need to break the task up into more manageable pieces. Typically, we can split the task by business function and is often the case those functions are mirrored by the organisational structure of the company. Start at the top of the Organisation Chart and work down until you identify an area that you think is manageable in a single sitting. I can’t tell you how much is manageable; that comes with experience and will vary from one organisation to the next depending on how comfortable your people are in a workshop environment. What I would say is to try to keep the workshops short, typically no more than three hours; two is better, with at least one decent break in the middle.

How many people do we need? Again we must be careful not to overload the meeting but equally, the more people you can get means you have more knowledge and experience to draw from. Any more than nine or ten is getting a bit heavy, anything less than three or four people might mean you are underrepresented and the results overly influenced by individuals.

If you do end up with a larger group, then consider splitting the group into smaller teams to work in parallel. This will help to hear the “quieter voices” in the room and ensure the results aren’t skewed towards the more dominant characters (everybody knows who they are!). Then bring the group back together and consolidate the results.

Step 1 - Capture

We will look at practical examples of modelling later in Chapter 14, when we will discuss the integration of data from different but similar retail outlets. For now, I’ll use a separate example of Hailer, a fictional ride-sharing service along the lines of Uber or Lyft.

Typically we’d ask the workshop attendees to talk about or write a brief description of the process we’re interested in. In this case, I’ve written down a brief user story based on my own experience of using such services.

A customer uses the Hailer app to hail a ride from their current location specifying the destination and number of passengers. The app identifies suitable vehicles, available or shortly to be available in the local area and alerts those drivers of the new request indicating the estimated value of the ride. The ride will be assigned to the driver who first accepts it. The app will then inform the customer of the driver details and estimated pick up time and the customer will be notified an estimated pick up time. On arrival the driver will confirm the pick up and the journey begins. At the end of the journey, the passengers will be dropped off, and the app will calculate the cost of the journey, based on the route, time taken and any road tolls incured. The customers credit card (that is attached to their Hailer account) is charged, and a payment sent to the driver.

Now we have the stories, we simply list out all the key nouns and verbs. I’ve highlighted the terms as follows.

A customer uses the Hailer app to hail a ride from their current location specifying the destination and number of passengers. The app identifies available (or shortly to be avalable) vehicles in the local area and alerts those drivers of the new request indicating the estimated value of the ride. The ride will be assigned to the first driver who accepts it. The app will then inform the rider of the driver details and estimated pick up time. On arrival the driver will confirm the pick up and the journey begins. At the end of the journey, the passengers will be dropped off, and the app will calculate the cost of the journey, based on the route, time taken and any road tolls incured. The customer’s credit card (that is attached to their Hailer account) is charged, and a payment sent to the driver.

The highlighted items are entirely my choice from my point of view, and other workshop attendees will have their own list, which we need to bring together and categorise.

Step 2 - Categorise

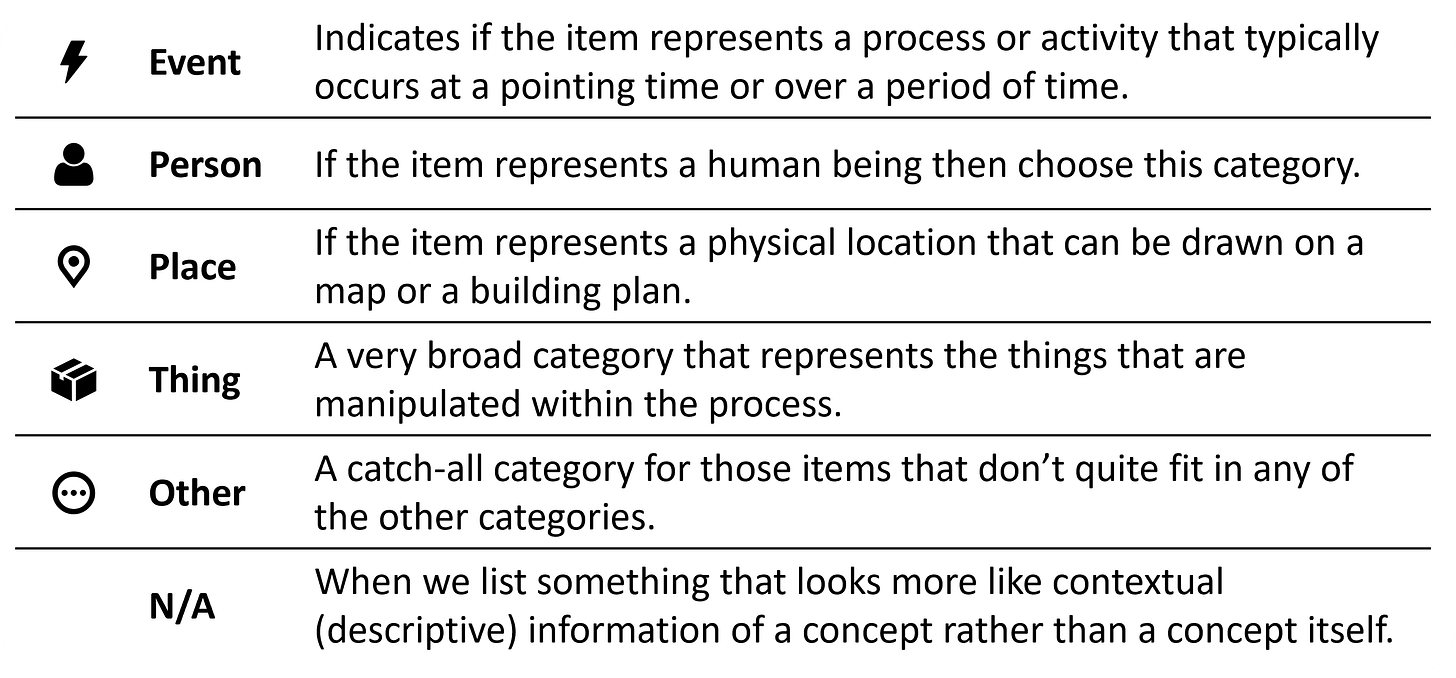

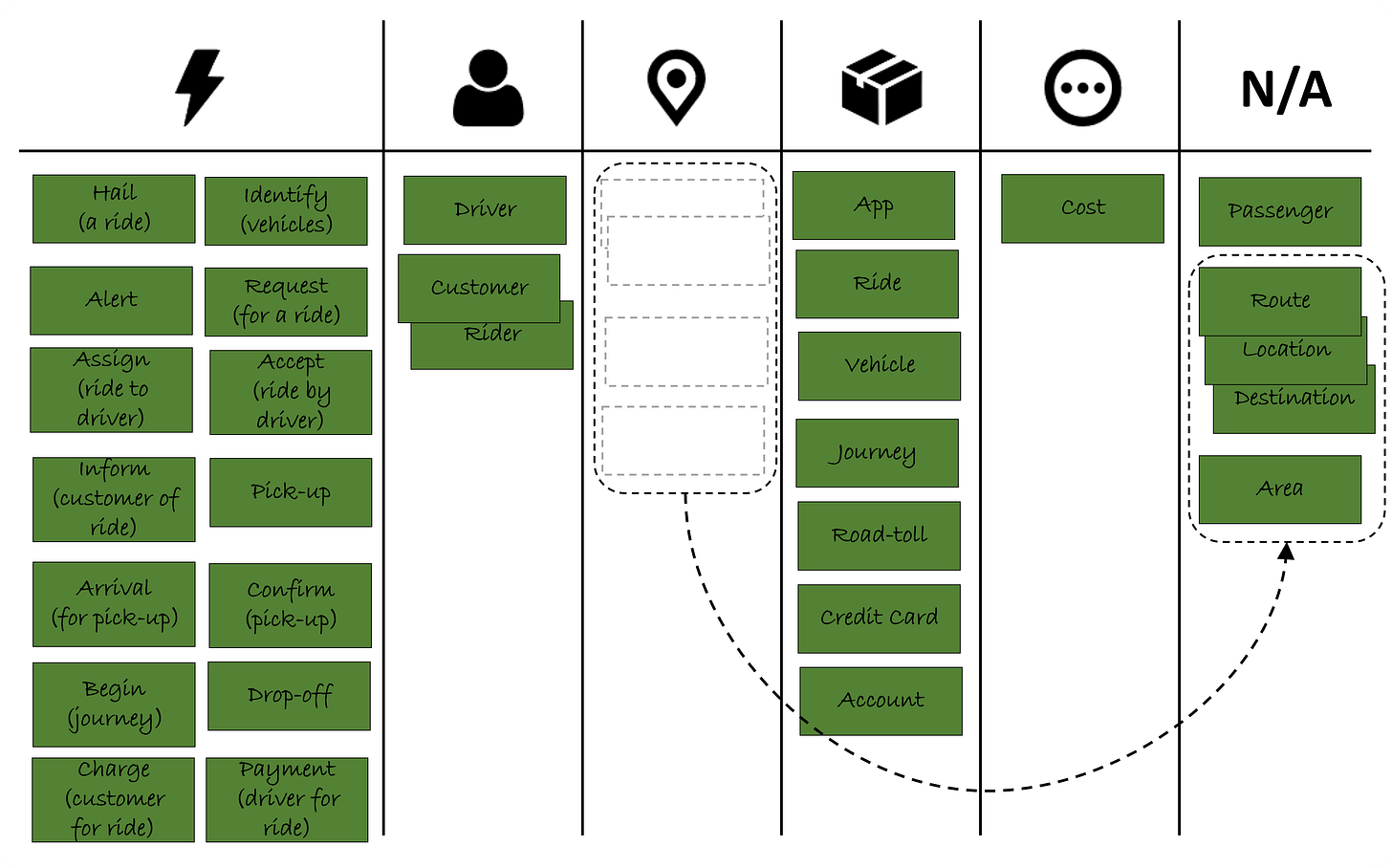

We then place all of the highlighted items in a list (known as the CBC canvas) and assign each to one of five categories.

Of course, this set of categories is not cast in stone. You may decide to include other categories. For example, you might decide to have a category of Organisation. Just be mindful not to include too many, as this will limit your ability to consolidate terms.

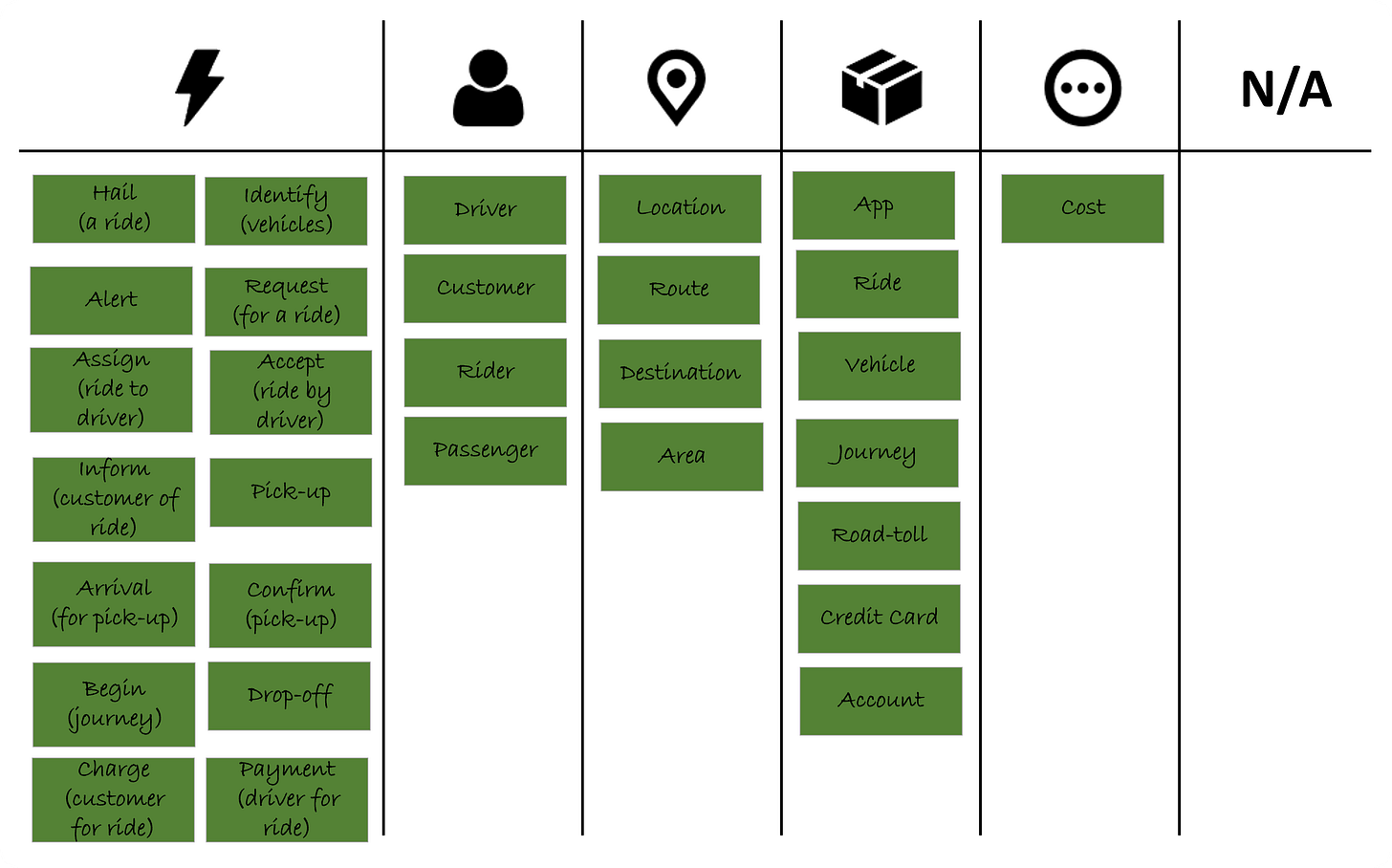

Working through the highlighted terms, I placed them on the canvas as follows.

You might disagree with the items I’ve picked out or the way I have categorised them, and that is entirely normal. If you gather together any number of people, particularly if they are from different parts of the business, there is little chance that there will be consensus, but that’s OK. The point is that we have captured the information, and once we’ve done that, we can move to Step 3 to consolidate terms.

Step 3 - Consolidate

In all likelihood, especially if you have obtained items from different sources, there will be some duplication, so we need to consolidate them. Often this step can feel like a negotiation; there will be lots of to-ing and fro-ing with differences of opinion. Healthy debate is a good thing, but the moderator of the workshop needs to make sure it doesn’t get out of hand, and if some disagreements get too heated, then they should be parked, and the conversation moved on.

There is no right or wrong way to tackle the consolidation exercise, but try to be methodical. Rather than bouncing around the canvas, focus on one category at a time.

Events are a special case, as we’ll see in Chapter 9, so we’ll leave that for now and start with the Person category.

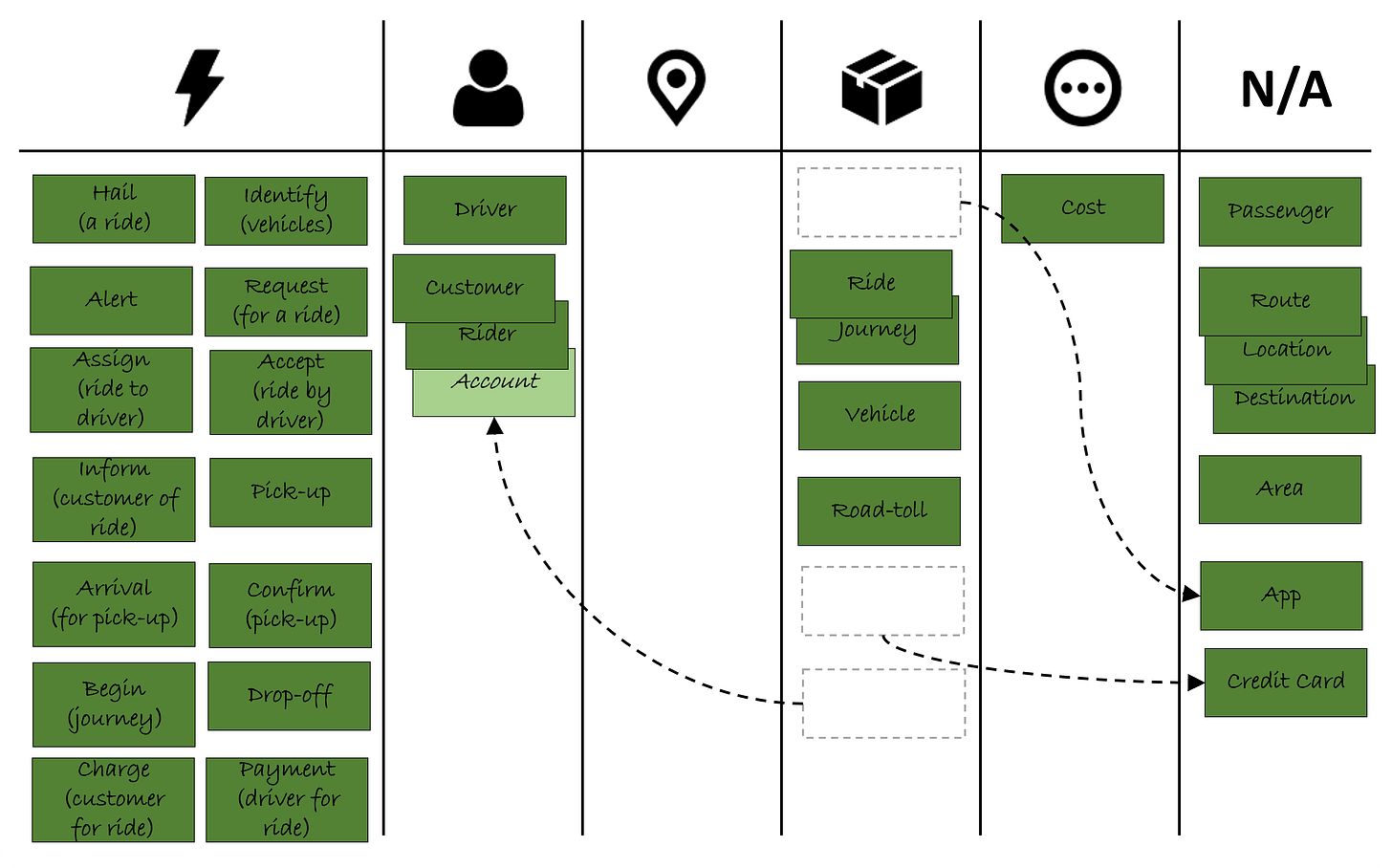

Driver, Customer, Rider and Passenger are all concepts we identified as people. The first thing we need to decide is whether they are legitimate concepts that, as a business, we care about.

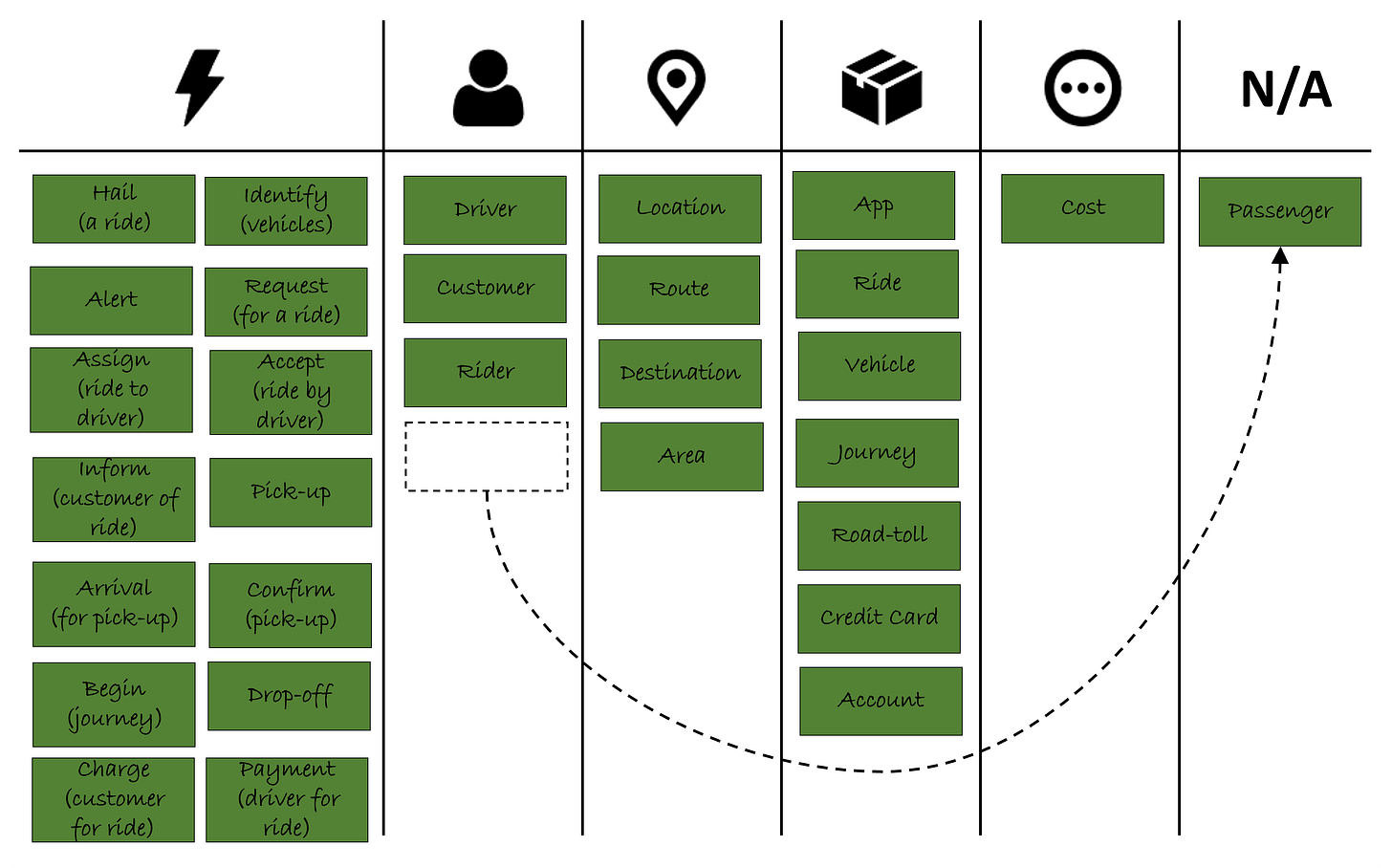

The first thing I would question is whether Passenger is a concept of interest. Of course, this depends entirely on our definition of a passenger. Is a passenger the same thing as a customer? I would argue that if a customer is a person who hails the ride, then the passenger is any other person that travels with the customer. From a business perspective, we don’t know anything about a passenger, only how many to expect for a particular trip. Therefore, the number of passengers is contextual information, so we can remove the term and move it into the N/A column, as shown in Figure 8.2.

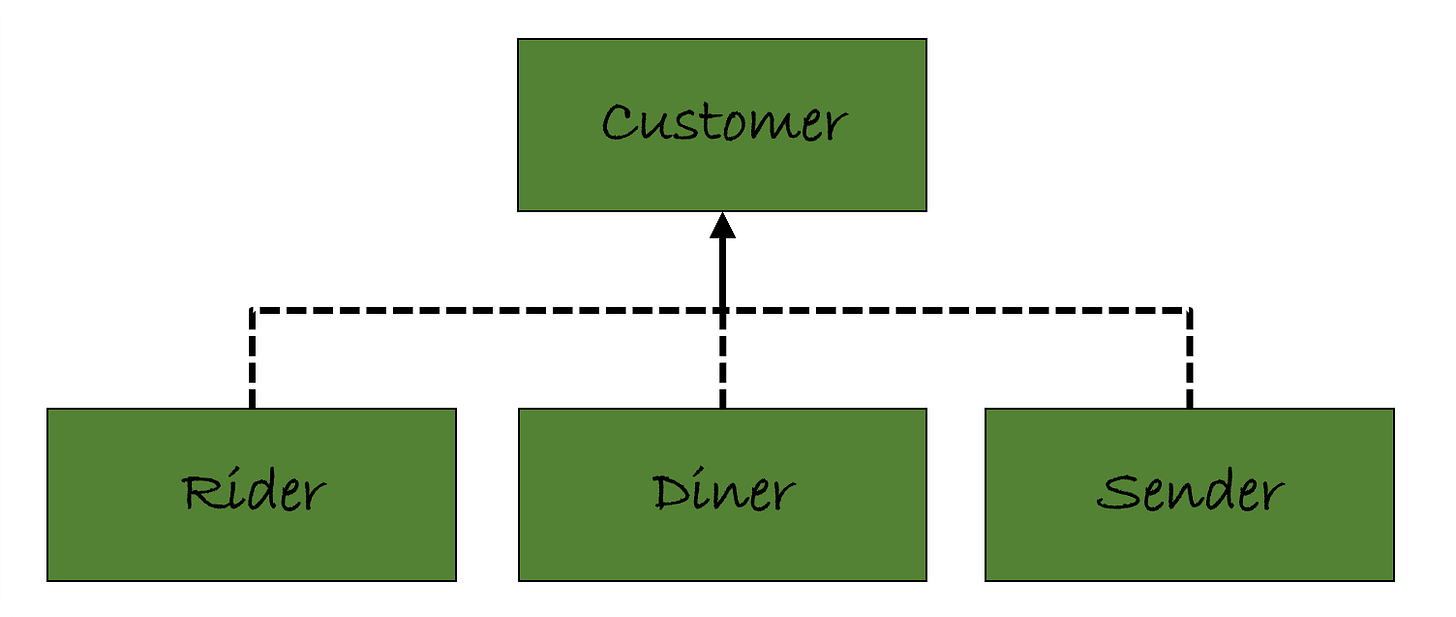

The next things to consider are the terms Customer and Rider. Are they the same thing? Based on the information we have available to us at the time, then it looks very likely that they are exactly the same thing. If that is the case, which term should we use? Customer is a more generic term, whilst Rider is more specific and relevant to this particular business process. Maybe we should be using the term Rider. However, we are only looking at one part of the business. What if the Hailer business also uses its network of drivers to deliver food or to deliver parcels? In those scenarios, there is no rider. If we were to perform the same CBC analysis for the food delivery service, we’d identify a different set of terms. We might, for example, identify a Diner as a customer who has ordered the food. For parcel deliveries, the customer might be called a Sender. So we have three types of customers which we can represent as a taxonomy, as shown in Figure 8.3.

I’ve thrown in the terms Diner and Sender to illustrate that there may be more to consider. Therefore, we need to try and think around each of the concepts. Question everything. I’m not going to say we should be using Customer rather than Rider in this situation, but I would suggest this might be prudent. But even if we do, there is no need to lose sight of the fact that Rider, Diner and Sender are special types of Customers. We simply document that these terms exist either as part of taxonomy or as synonyms within the Customer concept definition.

Next, we’ll look at the Place category, where we have Location, Route, Destination and Area concepts.

The Area was identified as an arbitrary boundary that encloses drivers/vehicles that could potentially be available to service a ride. Is an Area a concept we care about? Is there any information we might want to record against it? Probably not, and it is something we could derive based on tracking information, so we move it across to the N/A column.

(Pick-up) Location and Destination? They are both points on a map, where the ride starts and where it ends. Other than that, they are exactly the same. They are both just locations, and we can consolidate them under the term Location. Again, we can document in the definition of Location that it is also known as (synonym) of Destination. On the canvas, we gather the two terms together, placing the preferred term on top.

Finally, Route. Is this a place? You would argue that it is, as it is something we can draw on a map. Is this a concept that interests the business? Definitely! I imagine that the company will be able to glean a great deal of intelligence by analysing routes. But, is a route a CBC? We could argue that Route, as well as Location, is simply contextual information which can be attributed to a Ride. I suspect that the discussion around these concepts could get interesting, and if I’m honest, I don’t know the answer.

Maybe none of these terms is a CBC at all! Does a route itself have any contextual information? Do we give it a name? Will we ever want to refer to it in isolation and assign attributes to it1? We might decide that for this business, all this locational information is simply context, and none of them is a CBC. We can move them out to the N/A column, but we need to keep a note of what this locational information is associated with (Rides/Journeys). Figure 8.4 shows the result after all these decisions have been applied.

Again these decisions are just my assumptions, and you may have different views, which would be discussed/resolved in the workshops.

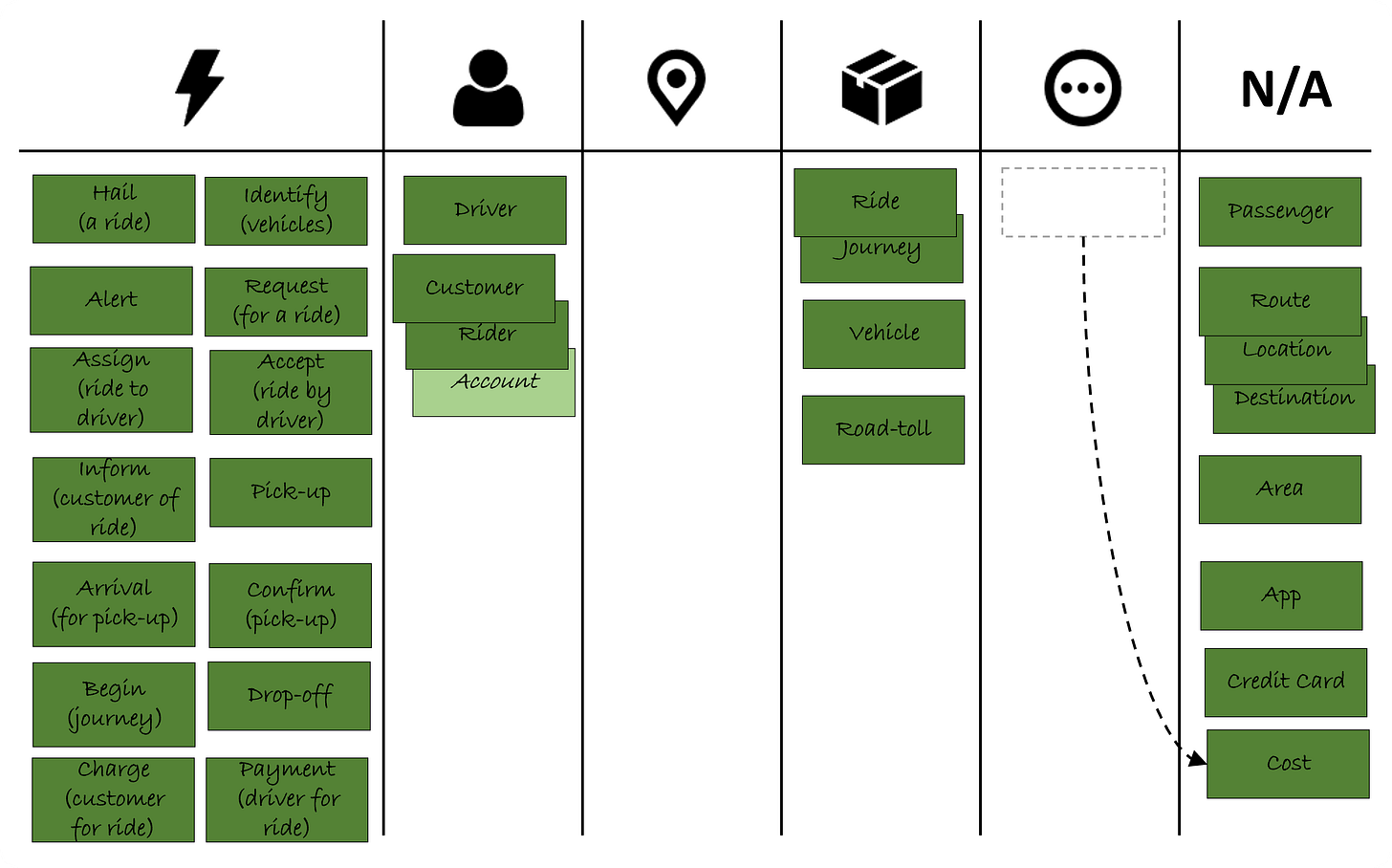

There seems to be a bit more variety in the Things column. Starting from the top, we can scan the list and see if there are any terms which might be similar.

In the user-story, the term App is mentioned a few times but is it a CBC? If there are different versions of the app that have different features, then it might be an important concept to the business but let's assume, in this case, it is not. We can move it into the N/A column.

Next, we have Ride. We’ve already talked about this when we discussed that the locational information was contextual information for Rides. That should give us a clue that the ride itself is an import CBC. If we scan down the list further, we also have the term Journey. Are they the same thing? I think it is safe to say that they are, so we must decide which term we want to use. Let’s go with Ride, but again make sure we record that Journey is a synonym.

The third item on the list is Vehicle. Nothing too controversial about this term, but we might want to ask some questions about the concept. For example, when we say vehicle, are we concerned with different types of vehicle. A vehicle could be an automobile, a bus (mini or full-sized), a motorbike with a sidecar or a train/tram. Thinking even more outside the box and into the future, a vehicle could be a helicopter, a personal drone or a quantum teleporter (OK the last one is a bit far-fetched). The point is there might be other CBCs hiding behind the scenes waiting to be discovered. We might want to list these different vehicle types as examples in the definition or even subtypes in a vehicle taxonomy. For now, we’ll just stick with Vehicle.

Road Toll. We could argue that this is simply contextual information to record against a Ride. Conversely, we can argue that we do need to track all road tolls as they have a lifecycle of their own. Once created, we need to ensure that those tolls are paid, which might happen after a Ride is complete. Therefore, we decide that Road Toll does qualify as a CBC.

The last two items in this category are Credit Card and Account. We’ll deal with these two concepts together. What is an Account? It is something that a Customer creates when they sign up for the Hailer service. One Customer has one Account. One Account is only ever for one Customer. Therefore, Customer and Account are, in effect, the same thing. Does the same reasoning apply to Credit Card? In this case, then no, as it is perfectly reasonable for the same Credit Card to be associated with more than one customer. But is it a CBC? Are we interested in tracking credit cards or are they simply a means to obtain payment? Hailer is a transportation company, not a financial institution, so they probably aren’t too interested in any of the contextual information around credit cards. The credit card number is, therefore, simply contextual information relating to a customer.

The overall result will look something like Figure 8.5.

Finally, we have the Other category, where we have placed the Cost concept. This one is straightforward. A cost is rarely a concept in its own right and, in most cases, will be treated as contextual information for some other concept. The cost refers to the calculated cost of the Ride (once it has been completed). Therefore, it is contextual information for a Ride.

Figure 8.6 shows the final CBC canvas, but bearing in mind, we are still to deal with the Event type CBCs.

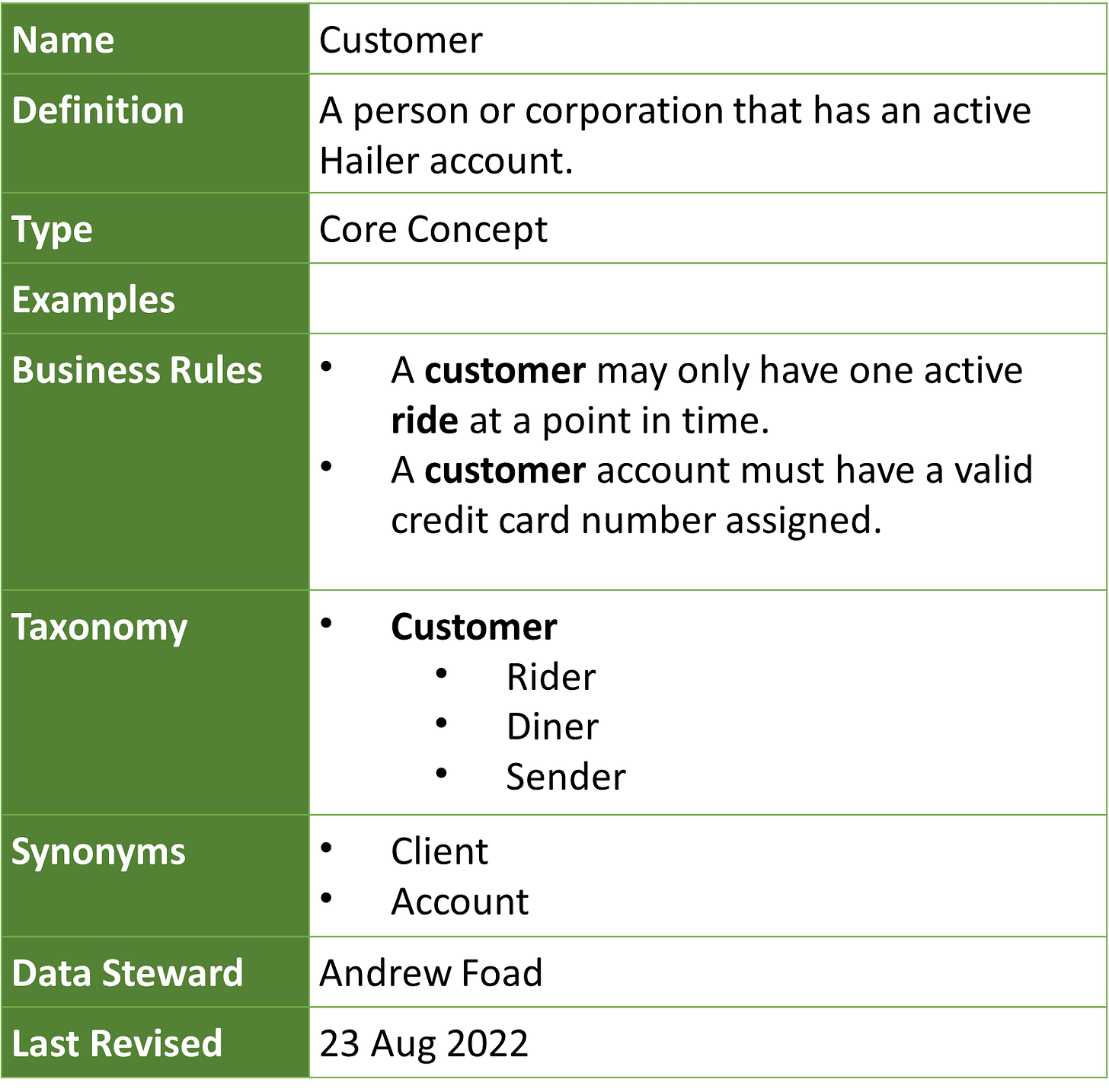

Step 4 - Define

The final step is to define each of the CBCs. After our consolidation efforts, we have been able to reduce the size of the list. We have:

Driver

Customer (Rider and Account)

Ride (Journey)

Vehicle

Road-Toll.

From a 150-word user story, we have been able to distil the list of core business concepts to a mere five concepts. If you showed the list to a complete stranger, they would probably get a pretty clear idea of what type of business we are talking about. It should be clear that we aren’t in the airline, hospital, or high-street clothing business.

And once we have our list of CBCs, we need to ensure they are properly documented and defined.

This activity can be done outside of the workshop and is the sole responsibility of somebody (the Data Steward) to obtain and document the information. For more information about business glossary terms, please refer to Chapter 3.

Summary

By tethering all data assets to a central set of CBCs, means that we are able to deduce how those datasets relate to one another even though we haven’t explicitly defined any relationships between them.

And this can be any type of data asset, not just those within the data warehouse. We can use the same core business concepts to underpin the following (amongst other) data assets.

Enterprise Data Model

Data Marts (Dimensional Models)

Data Warehouse (Hook, DV, etc.)

Application development

Messaging

Data Contracts

Knowledge graphs

…

This will help us to conform all data assets across the enterprise, regardless of where they are. Ultimately this will lead to better-quality data and clearer lines of communication.

Next Chapter

Not quite sure what chapter to publish next. Chapter 9 which will expand on Natural Business Relationship (NBRs), but at the current time, I haven’t written anything yet.

Substack has this poll feature so maybe give it a whirl. What would you like me to talk about next…?

Interestingly, to qualify as a licensed taxi driver in London, every driver must pass an exam known as “The Knowledge”. This requires the taxi driver to learn a set of approximately 320 predefined routes, known as ‘runs’, across the city. For a London taxi driver, the routes themselves are of great importance and can be individually identified.

I've read all the 8 chapters and found it really cool. I hope you will someday publish more. Thumbs up for your work

Do you have other chapters of this book written? Is it possible to buy it?