Chapter 0 - Introduction to HOOK

“You can please some of the people all of the time; you can please all of the people some of the time; but you can never please all of the people all of the time.”

- John Lydgate

Building software systems has been, and will always be, about compromise. As John Giles puts it in his book “The Nimble Elephant”1, software projects are a classic example of a zero-sum game; somebody’s loss equates to somebody else's gain. Ultimately, as software professionals, we are judged on how well we strike the balance between competing priorities.

Data Warehousing projects are no different. In the modern age of agile delivery, there is the promise of rapid and frequent delivery. Sadly in a data warehousing environment, this invariably leads to solutions which are poorly integrated, resulting in data siloes, which frankly defeats the entire point of a data warehouse, as we will see later on in this chapter.

To mitigate the threat of siloing, we need to take a broad view of the data landscape. One approach is to construct an Enterprise Data (or Conceptual) Model. We send out our business analysts to talk to subject matter experts (SMEs) from across the enterprise to gather requirements and gain an understanding of the business. The enterprise data modeller(s) then construct conceptual models with the aim to standardise and document the terminology used by the business during the day-to-day running of the organisation. Then, when we do start to build out the data warehouse, we can be confident that we have a good helicopter view of the organisation, which reduces the chance of our data warehouse data falling into siloes.

This level of modelling takes time. Furthermore, the resulting model is something that can never be 100% correct. There will always be discrepancies and conflicts to resolve, and in a fast-moving world, any model we build will see reality drift away from it; we are always playing catch-up. And while we are doing all this, we haven’t built a single thing in the data warehouse.

As the saying goes: cheap, fast and good; pick any two. Given that cost is not something we can easily play with, there is an implied trade-off between speed of delivery and quality of deliverables. Prioritise one, and the other one suffers. It seems we have a trade-off we cannot resolve.

Given the choice, any self-respecting software engineer would opt to prioritise quality over speed of delivery. After all, they know they will most likely be the ones tasked with supporting and maintaining the data warehouse long into the future. Short-term gains will lead to long-term pains! Unfortunately, data engineers never get to make these decisions. When push comes to shove, and a choice has to be made on which priority wins out, in most cases, we fall back to the default position of pleasing the customer. After all, they are footing the bill. We are invariably asked to deliver quickly, and told that we can address the inevitable deficit in quality “later”. Sadly “later” never comes, and our beautifully envisioned data warehouse is buried under increasing piles of technical debt that nobody wants to pay. It happens. Every… single… time.

“Surely, there has to be a better way?”

- Said every frustrated data engineer that ever lived

As a frustrated engineer, or at least as somebody who has known a few, I’ve seen this happen over and over again, and I often found myself asking this very question. What if we could “have our cake and eat it”? What if it was possible to quickly deliver the data warehouse without racking up mountains of technical debt, or at the very least creating technical debt that is much easier to digest? Wouldn’t that be something? And so HOOK was conceived.

As you will see, there is nothing new or revolutionary about the HOOK approach. If you have worked in and around the Data and Analytics space in the past few decades, you will be familiar with Ralph Kimball’s Dimensional modelling or Dan Linstedt’s Data Vault. These methodologies have been applied to the data warehouse with varying degrees of success. As you will see while reading this book, HOOK borrows heavily from their work. If you are comfortable with star schema or hub and spoke designs, then you’ll be right at home with HOOK. However, you will see that HOOK takes a slightly different approach.

Before delving into the WHAT and HOW of the HOOK approach, we need to understand WHY we need it.

What is a Data Warehouse?

Data Warehousing is not a new thing; Bill Inmon, widely regarded as the father of the data warehouse, coined the term back in the 1980s, and you would have thought that we would have figured it out by now. Yet, every day, we read stories of projects going off the rails: late delivery, budget overruns and solutions that are not fit for purpose. It keeps happening.

I have a theory about why this happens, but before we get into that, we should probably make sure we have a common understanding of what we mean by “Data Warehouse”.

The title of this book is “The Hook Cookbook: Data Warehousing Made Simple”, so we should be clear on what we mean by a “Data Warehouse”. I’m sure you will have some notion of what a data warehouse is, but can you define it?

Bill Inmon, widely regarded as the father of the Data Warehouse, originally came up with this definition.

“A data warehouse is a subject-oriented, integrated, time-variant and non-volatile collection of data in support of management’s decision-making process.”

~ W.H. Inmon circa 1990

Inmon has since revised this definition, largely in response to the growing popularity of the Data Vault.

“A data warehouse is a subject-oriented, integrated (by business key), time-variant and non-volatile collection of data in support of management’s decision-making process, and/or in support of auditability as a system-of-record.”

~ W.H. Inmon (circa 2018)

Of course, other definitions exist. In the 1990s, Ralph Kimball introduced dimensional modelling as an approach to data warehousing, focussing more on making enterprise data easier to access and query.

“A data warehouse is a copy of transaction data specifically structured for query and analysis.”

~Ralph Kimball

Kimball’s definition is valid, but for me, the Inmon definition, particularly the revised version, is more robust. But I will point out that the two definitions are not mutually exclusive, which I will touch upon later in the book.

Of these two definitions, I prefer Inmon’s, particularly the 2018 revised version, and it is the definition I have kept in mind while developing Hook.

I have highlighted four terms in this definition, which I call the Inmon Criteria[1]. I will revisit these criteria in Chapter 1 (Architecture) to demonstrate which parts of the architecture HOOK targets. So what do each of the criteria mean?

Subject Oriented

It depends on what you mean by “Subject”, but the essence of this criterion is data within the data warehouse should be organised around the Business vocabulary. We want to use business terminology, not the terminology used within the originating source system. For example, an HR system may refer to employees as clients. The term client might have no meaning to the Business, so why use it within the data warehouse?

Integrated

All too often, data loaded into the data warehouse remains aligned to the originating source system, which leads to siloes of data that are difficult to navigate. Data relating to a business concept, such as Customer, might be found in more than one source system. Can we easily answer the question, “Where is my Customer data?” We need to integrate the data from all source systems so that all customer data is logically (sometimes physically) grouped within the data warehouse. According to Inmon, integration implies that the data is transformed into common structures. Transformation of data is not strictly part of a HOOK Warehouse as we will see later, but it does make provision for it.

Time-variant

Whereas an operational system will maintain an “as-current” view of its data, the data warehouse should provide a historical record of all events. The data warehouse will record any changes from the source system (if provided) as new data. You can think of the data warehouse as providing a fossil record of the business’ activities.

Non-volatile

As with fossil records (and putting religious arguments to one side), we cannot change historical data. We must chronicle the facts as they occurred. Once recorded, we can never change them. And so it is with the data warehouse. Once we have stored the data, we cannot change it. The data is immutable. However, data within source systems are updated frequently, so the data warehouse has the responsibility to record those changes as new facts whilst retaining previous versions of the data. Therefore, the data warehouse provides a full audit of events[2]. How we interpret that historical record is a different matter.

In addition to these four criteria, I will also draw your attention to one of the changes Inmon made to his 1990 definition. The addition of “(by business key)” has enormous significance in the Hook approach. Arguably, the treatment of the humble business key is what distinguishes Hook from other data warehousing methodologies.

Not all agree with these criteria. Kimball’s dimensional modelling approach does not meet the ‘Non-volatile’ criterion, which is understandable as its goal is to facilitate reporting capability. However, maintaining history in a dimensional model can be challenging and lead to overly complex and resource-heavy processing pipelines.

To a lesser degree Data Vault also fails to meet these criteria. In trying to be all things to all people, the Data Vault methodology talks about the business vault, point-in-time satellites and bridge tables to boost querying performance, but these constructs all fall outside the ‘Non-volatile’ criterion.

Hook, however, adheres strictly to the Inmon criteria, and in that regard, knows exactly what part it plays within the architecture of the overarching data platform. I will discuss this in more detail in Chapter 1 - Architecture.

A Short History of Data Warehousing

Data Warehousing as a subject is still something we haven’t quite solved. There isn’t a commonly accepted way to “do data warehousing”. As a concept, data warehousing is a relatively new idea, and there have been many attempts to standardise an approach that works universally. To set the scene for the rest of the book, it is worth considering the history of data warehousing to see how it has evolved as a subject over the past three or so decades. It is widely recognised that there are three main influencers in the field of data warehousing, and I will touch briefly on each of their contributions.

Bill Inmon

Widely acknowledged as the father of data warehousing, William H. Inmon, coined the term “data warehouse” in the mid-1980s. Inmon’s definition of the data warehouse, as we’ve just seen, is as relevant today as it was back then.

Inmon’s vision of the data warehouse required data to be extracted from business-focused operational systems, transformed and then loaded into a common normalised database structure. The normalised structure is a top-down logical data structure that is a digital representation of the overall business. Indeed, the term ETL (Extract-Transform-Load) has become synonymous with any data transformation activities, even outside of data warehousing. It is a wonderful vision, but the practicalities of building such a data warehouse in this way have always proved challenging.

The target of an Inmon-style data warehouse (as it was originally conceived) is a third normal form style data structure with an added historical dimension. A description of the various levels of data normalisation is far beyond the scope of this book, but I always found the following amusing quote from Chris Date (Date, 2003), which states that for a third normal form data structure, every attribute must depend upon…

… the key, the whole key and nothing but the key (so help me Codd).

I’m not sure who added the “so help me Codd” bit, but this is a nod to Edgar F. Codd, who pioneered the work on the relational model and its various normalisation forms. The aim of Third Normal Form is to create structures that eliminate data redundancy. That means that any singularly identifiable piece of information is recorded once and once only, so if it needs to be changed (updated), then it only needs to be done in one place. This ensures the integrity of the data is maintained, making it impossible, or at least extremely difficult, for the data to contradict itself.

This type of modelling is easy to get wrong. In a sense, it is often seen as a dark art requiring the data modeller to conceive concepts that are not always obvious. The enterprise data model is a representation of the whole business, and as such, it isn't easy to develop such a model in a distributed manner. There will be concepts that overlap from different parts of the business but could have different meanings. At some point, a consolidated view needs to be formed with a common vocabulary.

By definition, therefore, the enterprise model has to be developed or at least managed centrally. This centralised governance is often a bottleneck in larger organisations. If the organisation of the data warehouse depends upon a common centralised model, then any attempts to distribute development effort will be greatly hindered.

In other words, centralised modelling restricts our ability to scale. If we do need to scale, then we have little choice but to compromise on the modelling by allowing local models to be built, which, as you might have guessed, leads us down the rocky, yet inevitable, path to data siloes.

Ralph Kimball

Kimball-style data warehouses were all the rage a decade or so ago. In hindsight, this wasn’t because the method was particularly robust, at least not in terms of sound data warehousing practices, but rather because it was easy to understand.

In essence, the Kimball data warehouse is an implementation around a star schema. Some have described it as a “Star schema with history”. The structures are extremely simple. Essentially just two types of table, namely dimensions and facts. The dimensions track business keys and associated contextual (descriptive) information, and the facts record measures or metrics around the intersection of those business keys.

Kimball formalised this simple concept into an entire methodology. Dimension tables represent business concepts and their descriptors. Fact tables represent business processes and the metrics that we can use to measure their performance. Documenting the intersection between dimensions and facts is presented in the form of the BUS matrix, an amazingly simple yet powerful way to visualise how the assets within the data warehouse hang together.

A fantastic idea that doesn’t really work, at least not for the purposes of a data warehouse. The main issue I have observed is that dimensional data warehouses are extremely easy to build but incredibly difficult to change. Every single artefact within the data warehouse represents a bottleneck, and as such, it is almost impossible to distribute and scale development within a Kimball data warehouse.

Dan Linstedt (Data Vault)

Out of the work he did with Lockheed Martin in the 1990s, Dan Linsedt developed the Data Vault methodology. Initially, this was simply a modelling approach, that evolved into a full-blown methodology. The first iteration, now known as DV1.0, was optimised for traditional centralised databases, and has since been superseded by DV2.0, which shifted the methodology towards distributed databases and, more recently, cloud technologies.

The methodology is designed to scale, at least in terms of build activities. It is easy to extend an existing Data Vault data warehouse with an “add, don’t change” approach. In that sense, DV2.0 is agile and scaleable, but only from a build perspective. In terms of modelling, then Data Vault suffers the same issues as the approaches pioneered by Inmon and Kimball.

Personally, I’m a big fan of Linstedt's work which has been a huge inspiration for the

Hookmethodology. The contribution Dan has made to the industry is profound, but time marches on and new technologies require new methods.

The Modern Data Stack (MDS)

And then along came the Modern Data Stack or MDS. The idea is that, if presented with the right set of tools and technology, then we don’t really need a data warehousing methodology. Just dump all the data into a central store and sort it out afterwards. It’s an appealing proposition. It allows us to kick the can down the road. Let’s not worry about modelling the data; if we can get all the data in, we can worry about that later. It’s an extraordinarily liberating and equally stupid line of thinking. The notion that we can solve the problem we call the data warehouse with technology alone is simply dumb.

But here we are, with cloud infrastructure growing exponentially with offerings from Microsoft, Amazon, Google and others. The choice of services is mind-boggling. The rate at which they are made available to us, even more so, to the point where we have forgotten the important stuff. Model data? Govern data? Integrate data? No thank you! I’m too busy trying to keep up with all the shiny new toys that all these vendors throwing at me. It’s exhausting.

Why do Data Warehouse projects fail?

Having an identity crisis about what does and what does not qualify as a data warehouse is not the reason why so many of these projects fail. If followed correctly, the Data Vault approach should serve you well.

If … followed … correctly.

These three words highlight the crux of the problem, which has nothing to do with the methodology itself. The problem is that we, more often than not, don’t follow the prescribed standards. We know it is the wrong thing to do, yet we are compelled to do it all the same. Why does this happen? Let me give you an example of how. What I am about to describe is a situation I’ve encountered on many occasions with different clients. I base this discussion around Data Vault examples, though I’m sure the same problems would arise regardless of the methodology you used. By no means is this a criticism of Data Vault, but rather the environment in which we try to use it.

As one of the few Data Vault ‘experts’ at the consultancy firm I happened to be working for at the time, I was often brought in on projects to offer guidance to the delivery streams. On arriving, certain decisions had already been made.

The client wants to use Data Vault, although no reasons were given to back up that decision.

The first use-case had been identified. The source system and the reports that needed to be created from the data had been identified.

A development team had been hired, but none had been formally trained.

Deadlines had been set. Deliverables were expected within six months.

A Data Vault automation tool had been purchased. A POC (proof of concept) was in progress. If the POC failed, the delivery deadlines still stood.

Given these constraints, it seemed unlikely that timely delivery was possible. Adding anything else into the mix would only make matters worse, so you can imagine the responses I got when I suggested that they really should consider doing some form of enterprise data modelling/architecture before we started the Data Vault modelling.

Client : “How long is that going to take?”

Me : “That depends. We don’t need to go into great detail, but we will need a broad scan across the Business. If we can identify and interview the appropriate stakeholders, we can probably pull something together in a month, maybe two.”

Client : “That’s going to be challenging. We generally struggle to find suitable people from the Business willing to offer their time. And we don’t have the time. We have committed to delivering these reports within the next six months. We cannot afford to wait.”

Me : “So you understand you will have a lot of rework in the future.”

Client : “Yes, yes. We can tackle any technical debt once we’ve delivered the first tranche of reports. After all Data Vault is extremely agile.”

Sadly, technical debt is rarely, if ever, addressed adequately. There is always more important, higher-value work to be done. And as with any type of debt, if left unpaid, it accrues and compounds interest …

Leading proponents of the Data Vault methodology will tell you that it is essential to invest in a foundational business architecture before embarking on a Data Vault implementation. I would extend this argument to any data warehouse initiative regardless of methodology.

Unfortunately, this modelling exercise presents a bottleneck, preventing any development work from proceeding until it is “done”. The obvious solution is to remove the bottleneck entirely and dive into design and build activities. Initially, progress will be rapid, but the reality is that as soon we decided to bypass the enterprise modelling, we effectively planted a time bomb in the data warehouse. When the bomb goes off, and it surely will, we will find ourselves staring down the barrel of another failure. Let me explain.

Technical vs Business View

Although this book concentrates on data warehousing, the problem described in the previous section is not unique to data warehousing projects. Rather, it is the age-old disparity between IT and Business, where the two parties try to communicate with one another whilst using entirely different languages. IT and Business see the world in very different ways. The Business lives in the “real world” where things are messy, nebulous and prone to change. IT folk live in the “digital world” where everything has to be precisely defined and organised. Is it any wonder that they struggle to communicate?

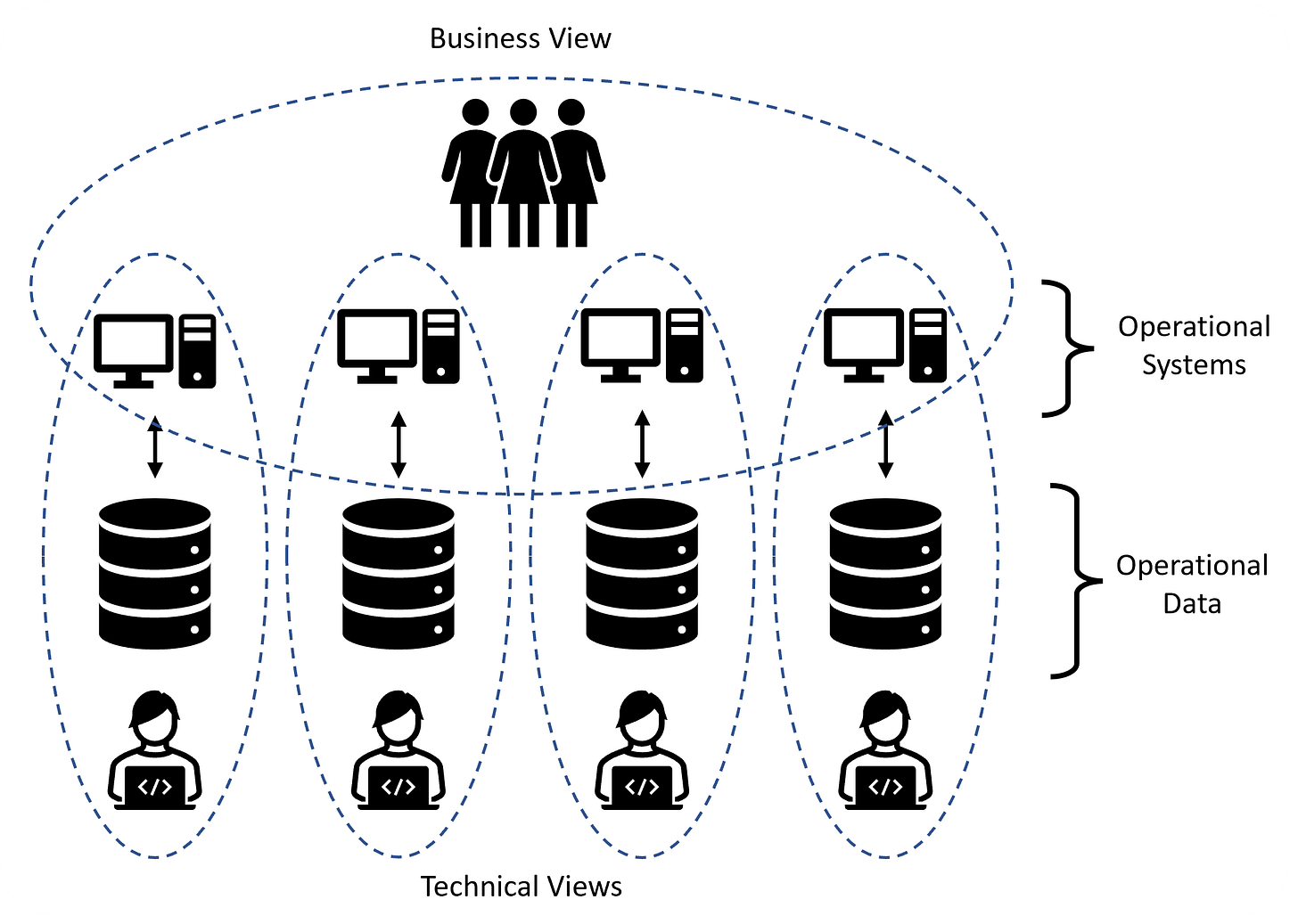

Consider Figure 0.1, which represents data contained in four operational systems.

At the top of the diagram, looking down (Top-Down), the Business views the data in these systems holistically, primarily through the use of operational applications. The scope of their interest is broad across all the systems. However, they do not need to concern themselves with the details of how each of those systems operates under the covers. The Business uses enterprise-wide language; they tend not to use different terminology in different systems.

Conversely, the technical view of these systems (from IT) is from the bottom of the diagram looking up (Bottom-Up). The scope is narrow, focusing on one system at a time but not necessarily seeing the bigger picture. Consequently, IT uses language governed by the terminology used by each source system, which is unlikely to align with the enterprise/business terminology or the terminology used within other operational systems. IT effectively operates within a series of siloes, less unconcerned with anything happening outside.

Without any business modelling, data warehouse projects have no option but to operate in a Bottom-Up fashion. We are forced to develop functionality on a use-case by use-case basis. Typically, this involves looking at a subset of data from a specific source system to deliver a particular report.

When we bring data into the data warehouse from the first system, what terminology do we use to integrate the data? If the operational source system refers to the concept of a client, then we might be tempted to use that terminology in the data warehouse. This is fine for the first system we bring into the data warehouse, but what happens when we bring in the second system, which might refer to the concept of customer? Now, we have some tricky questions to answer.

Is a client the same thing as a customer?

Do we have definitions for these terms?

If they are the same concept, then which terminology is preferred?

If the new term (customer) we’ve just encountered is the preferred term, what is the impact of changing everything we’ve already built around the old term (client)?

You can imagine that as more and more systems are introduced to the data warehouse, the issues will begin to snowball to the point where it is simply too difficult to make changes. The alternative is to ignore integration on an enterprise scale and integrate locally; in other words, silo the data.

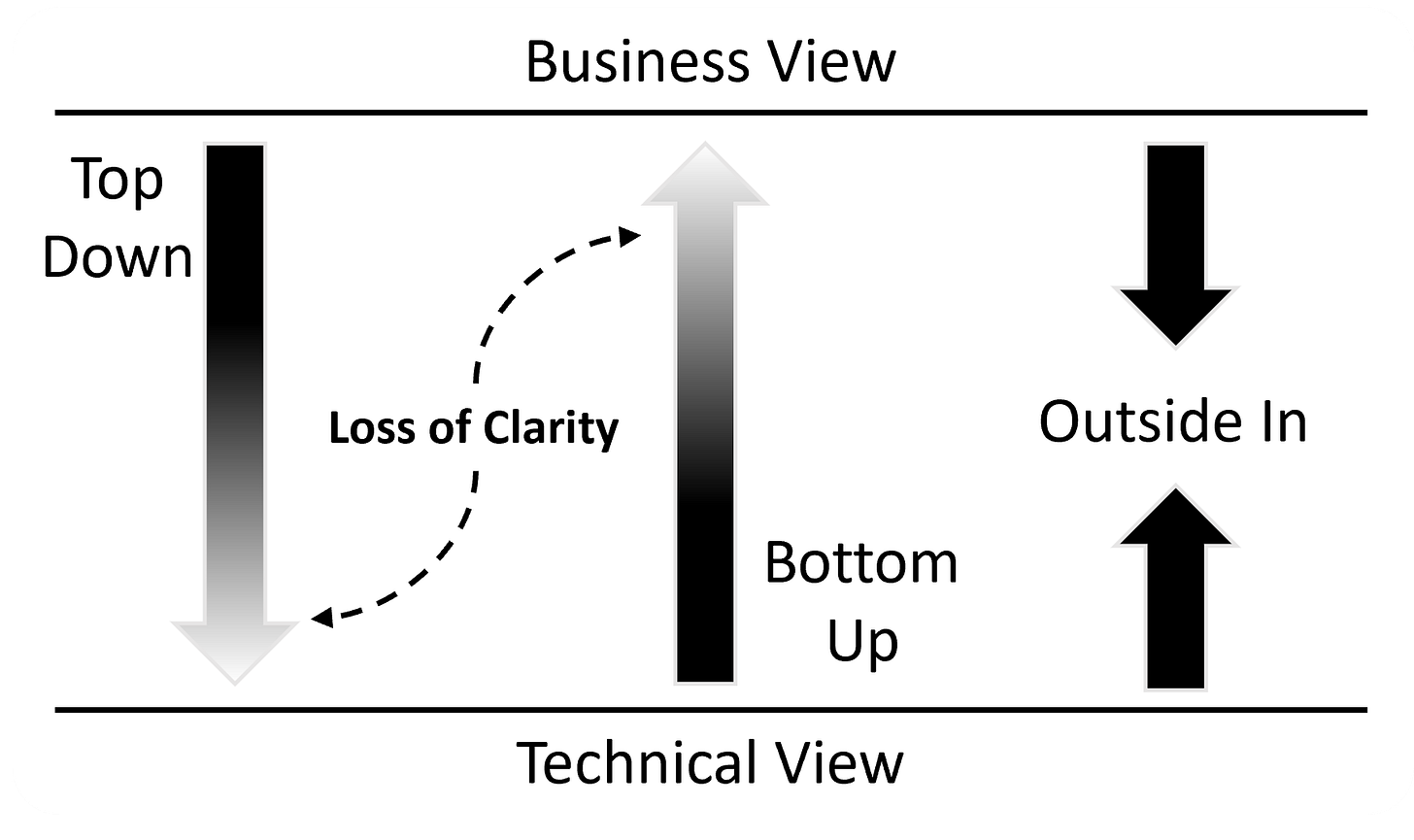

To summarise: the Top-Down approach is often unpalatable as it prevents us from proceeding until it is done (to an acceptable level of detail); Bottom-Up is even worse as we end up with siloed data that is unusable on an enterprise scale. Maybe we need something that sits between these two approaches…

Outside-In Philosophy?

If Top-Down and Bottom-Up approaches don’t work, is there another way? Is it possible to ingest data without modelling it? Is it possible to model the data without ingesting it? Can we somehow allow ingestion and modelling to proceed independently and then align the results after the fact? Is there a genuinely agile approach that enables model changes to be applied without ever having to reload data?

These are the kinds of questions that were keeping me awake at night, and the seeds of the Hook approach began to take root. And now, I can say that the answer to these questions is a resounding “YES!”

Whereas the Top-Down starts with a clarity of vision when talking to the business, that view becomes less certain as we try to reconcile with what we see at a technical systems level. The same applies when using a Bottom-Up.

The Hook approach is to work Outside-In, as shown in Figure 0.2. By decoupling business-oriented modelling efforts from technically-oriented system-level work, there is no loss of clarity. The two views can exist side-by-side. With Hook, the magic happens when they meet in the middle.

Summary

The aim of HOOK is to provide an approach to Data Warehousing that decouples data modelling activity from the business of data acquisition, which offers HOOK practitioners a great deal of freedom.

We will see in later chapters how this works in practice. Spoiler: it isn’t difficult!

Next Chapter

In the next chapter, we will discuss where HOOK fits into the overarching data architecture.

Giles, John (2012). The Nimble Elephant: Agile Delivery of Data Models using a Pattern-based Approach (1st edition, ISBN 978-1-9355042-5-2)

I like the way you have described the history of DW. Specially the phase I believe we are in now. All the vendors throwing platforms and tools at us but the tools or the platforms were never the "main" problem for us in DW-industry. It’s also funny to me (and sad at the same time): When attending both Hans Hultgrens and Dan Linstedts DV-courses, we are taught that both 3rd normal form or Dimensional Modeling approaches are bad and therefore choose DV..and then we end up using dimensional model to represent the DataMarts in a DV-DW. We end up having all the issues and benefits from DV and dimensional modeling in the same DW!? So practically we haven’t solved anything because to be flexible/scalable in DW-integration we used DV (and it’s not user friendly) and to make it user friendly we used Dimension modeling (which is not flexible). Ending up with 2 DW:s but we call in one DW. Then people in DV community will say, you don’t have to create a physical dimension model layer, just use view layer. To these people I say: It probably works in small DW:s but I have only worked with large enterprise DW (banking and telecom) and using views doesn’t really work when the users wants to analyze 10 years of historical data (transactions and call records)

I have been following your work and I saw in one of the videos that you need a real case hook-implementation. I am actually working with that now. My plan is to combine hook method and combine it with Puppini bridges. In this way we kind of combine best of both worlds. I just have to figure out how to “connect” hook keys with the concept of puppini bridges keys if you knw what I mean. I feel that something beautiful can be done here (combining hook and puppini keys)…just haven’t had the time to figure it out…yet.

I will keep you updated.

Looking forward to reading the next chapters. I resonated a lot with your problem setting and observations. Great work, Andrew